PILLAR 1: STRIVE TO BE TOXICS FREE

Many school facilities have been poorly maintained and thousands of our nation’s schools remain severely overcrowded. Schools are often sited next to industrial plants or on abandoned landfills…In a recent five–state survey, more than 1,100 public schools were built within a half–mile of a toxic waste site. Polluted indoor air, toxic chemical and pesticide use, growing molds, lead in paint and drinking water, and asbestos are also factors that impact the health of our nation’s students and school staff. These problems contribute to absenteeism, student medication use, learning difficulties, sick building syndrome, staff turnover, and greater liability for school districts.

—The Coalition for Healthier Schools21

Much of the debate around issues and conditions in our schools focuses on drug use, violence, budget cuts and test scores. But in the past decade parents, activist groups, educators and government officials have all paid a growing amount of attention to environmental health issues. And rightly so. Environmental health problems plague many of the nation’s 115,000 schools.

Once again, given the number of factors involved, it is difficult to make any absolute correlation. However, many childhood diseases are on the rise. For instance, asthma afflicts nearly 5 million children in the US, and is the primary cause of school absenteeism. Cancer is the number one disease–related cause of death in children, and the rates of many types of childhood cancer have risen. Childhood learning disabilities have also significantly increased nation wide. Many scientists believe that a great number of these diseases and learning problems can be related to children’s exposure to environmental health hazards in the womb and in their environment—including school.22

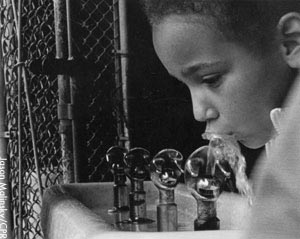

Poisoned Pupils

|

| Lead in soil, paint and drinking water continues to be a significant problem in many schools across the country |

As we’ve discussed, it is a somewhat stunning fact that schools across the country routinely expose children to pesticides. For instance, in the late 1990s, Connecticut schools reported 87% of 77 school districts surveyed sprayed pesticides indoors, where they could linger on desks, toys and other surfaces for up to two weeks. In Washington 88% of 33 school districts surveyed use one or more pesticides that can cause cancer, or damage the nervous system, hormone system or reproductive system. In California 93% of 46 school districts surveyed use pesticides; with the vast majority using one or more of 27 hazardous pesticides that can cause cancer, affect the reproductive system, mimic the hormone system or act as a nerve toxin.23 Of the 48 pesticides most commonly used in schools, 22 are classified by the US EPA as possible or probable carcinogens.24

The problem extends well beyond pesticides. The placement of a new school, or the location of new economic activity near an existing school can expose children and staff to significant environmental hazards. This is the case for instance, in places like East Liverpool Ohio, where a hazardous waste incinerator was located adjacent to an elementary school; or in Watsonville, California, where many schools are located next to agricultural fields and are exposed to pesticide drift. The exposure of school communities to such toxic hazards often involves questions of environmental justice, as the districts in which these hazards are located are frequently poor communities, and/or communities of color.25

Citing fifteen case studies from eleven states, a report by the Virginia–based Center for Health, Environment and Justice (CHEJ), asserts that new schools are routinely built on contaminated land, or near an industrial, commercial or municipal site that releases toxic chemicals into the air and community on a daily basis.

Astoundingly, no guidelines are in place to direct school districts where to locate new schools. Parents and communities across the US are shocked to find construction crews descending on abandoned landfills, brownfields, or next to heavily polluting industries to build schools. School districts, pressed to save money are often enticed by donations of unknowingly contaminated property, seek out the cheapest land, or hire uncertified or poor–quality contractors for environmental assessment; all at great risk to children. The poor and communities of color where children already suffer disproportionately from asthma, lead poisoning, and developmental disabilities, lose out most frequently.26

Poor indoor air quality is yet another issue. Many schools are plagued with mold. Others pack students into portable and permanent classrooms that off–gas volatile or semi–volatile organic compounds. Others have such poor

|

Asthma, exacerbated by polluted

indoor air, causes US kids to miss more than 10 million school

days a year

|

ventilation that children suffer. Symptoms identified include upper respiratory infections, irritated eyes, nose and throat, nausea, dizziness, headaches and fatigue, or sleepiness. Collectively these have been dubbed “sick building syndrome.”The American Lung Association found that American children miss more than ten million school days a year because of asthma exacerbated by poor indoor air quality. Schools serving poor communities, and often communities of color suffer disproportionately from poor indoor air quality.27

The presence of lead contamination also continues as a major problem in schools. For instance, thirty–two percent of all public elementary schools surveyed by the EPA in California had both lead–based paint and some deterioration of paint. Eighty–nine percent of all California schools studied had detectable levels of lead in soils, with 7 percent of the schools showing lead levels in soil at or exceeding the EPA hazard standard. Approximately 15 percent of schools had lead levels in drinking water that exceeded the EPA’s drinking water standard.28

De–Toxifying Our Schools

“The basic challenge,”says Forrest Gee, president of the school board in Emeryville, California, is “how to minimize a school’s impact on youth health.”29 In this regard, it is valuable to step back for a moment and envision what should be. So, imagine for a moment a toxics–free school. It shouldn’t be that hard—in fact it should be a fundamental point of departure for any school to ensure the children and staff both a safe and healthy environment, free not only of physical violence, but also free of pesticides, lead, asbestos and other hazardous materials. Imagine a school that uses alternatives to pesticides and herbicides, one that purchases green cleaning products, one that is built with environmentally sound materials, that has eliminated mold and other indoor air quality problems, that serves sustainably grown, organic, pesticide–free food, and that by doing so, sends a clear message to the children and the community.

|

Communities and networks

are organizing to make schools healthier

|

There are, in fact, a growing number of efforts to move us in this direction—to address these issues and to make our schools healthier places. For instance, the American Public Health Association recently declared that “every child and school employee should have a right to an environmentally safe and healthy school that is clean and in good repair.”For this to happen says APHA, “federal, state, and local entities must work together to use resources effectively and efficiently to address school siting, construction, maintenance, and other practices to ensure the provision of an environmentally safe and healthy school.”30

There are two nation–wide initiatives working to these ends—the New York–based Healthy Schools Network and the Center for Health Environment and Justice’s Childproofing Our Communities Campaign.31 Both these efforts work in coalition with various organizations from around the country to address everything from classroom air quality (especially toxic conditions in portable classrooms), to lead paint in older classrooms, to toxic chemicals at schools, to promoting green cleaning methods, to addressing mold, waste management and recycling.

The Childproofing Our Communities Campaign works primarily at the grassroots level with community–based organizations and networks. The Healthy Schools Network has developed a host of specific policy recommendations and guidance documents for national, state and school–specific decision–makers.32 And according to the Network’s coordinator Claire Barnett “the coalition participants have shaped and won new federal funds and policies for schools, and launched state–based coalitions in half a dozen states that are securing new state policies, regulations and funding streams.”33 For instance, in 2005 the Network, together with various allies won a commitment from the Governor of New York to submit a bill to the state legislature “that will require all public and private schools to use greener cleaning products.”34

Other issue–specific organizations and coalitions such as the national group, Beyond Pesticides, and the statewide alliance, Californians for Pesticide Reform, have been instrumental in moving focused agendas forward. For instance, as a result of these coalitions’organizing efforts, in recent years more and more states have adopted Integrated Pest Management guidelines for their schools. Today thirteen states require IPM, and four more recommend it.35

PILLAR 1: SPECIFIC STEPS FORWARD

Overall, some key steps in applying a Precautionary Approach to help make our schools toxics free might be the following:36

1. Parents, Students and School Staff Should:

- Demand from school administrators and district personnel the right to know about environmental health issues such as pesticides, commercial cleaning products, lead, mold, indoor air quality (especially in portable classrooms), and industrial emissions at and around school.

- Advocate that schools use alternatives to pesticides, herbicides and toxic cleaning materials whenever possible.

- Conduct a school health survey to identify possible problems in your schools.

- Pressure school districts, along with local, state and federal governments, to do the following:

2. School Districts and Local Governments Should:

- Provide parents, students and school staff with the right to know (see above).

- Ensure that schools are not sited near or on environmental health hazards.

- Adopt Integrated Pest Management programs and other policies to minimize or eliminate the use of hazardous pesticides and herbicides.

- Adopt policies that mandate using the least toxic cleaning materials.

- Ensure that new schools are built or refurbished using the least toxic materials, and with designs that minimize mold and maximize good ventilation (see Pillar 2)

- Serve sustainably grown, organic, pesticide–free food (see Pillar 3)

- Act on early warnings: where parents or staff have a credible fear about a particular issue, school districts and elected officials should take them seriously and attempt to address their concerns.

- Avoid the use of portable classrooms (which can off–gas formaldehyde) where possible, and ensure their ventilation when they are used.

3. State Education Departments and Governments Should:

- Adopt state–wide Integrated Pest Management legislation and policies such as the proposed California Assembly Bill AB 1006, which would eliminate the most highly toxic pesticides from schools.

- Adopt and fund standards that mandate the elimination of toxic cleaning and maintenance materials in state schools and/or the adoption of least–toxic alternatives.

- Adopt and fund standards that mandate new schools be built or refurbished using the least toxic materials as part of a set of healthy, high–performance schools standards.(pillar 2)

- Restrict the use of portable classrooms where possible.

4. The Federal Government:

- Congress should pass the School Environmental Protection Act (HR 121), which would require the implementation of Integrated Pest Management programs nation–wide.

- Congress should increase funding for EPA’s Indoor Air Quality Tools for Schools program, which provides technical assistance to local efforts to address problems.

- The US Department of Education should submit to Congress the long overdue and required report on the impact of unhealthy school buildings on child health and learning (Section 5414 of the No Child Left Behind Act, 2001).